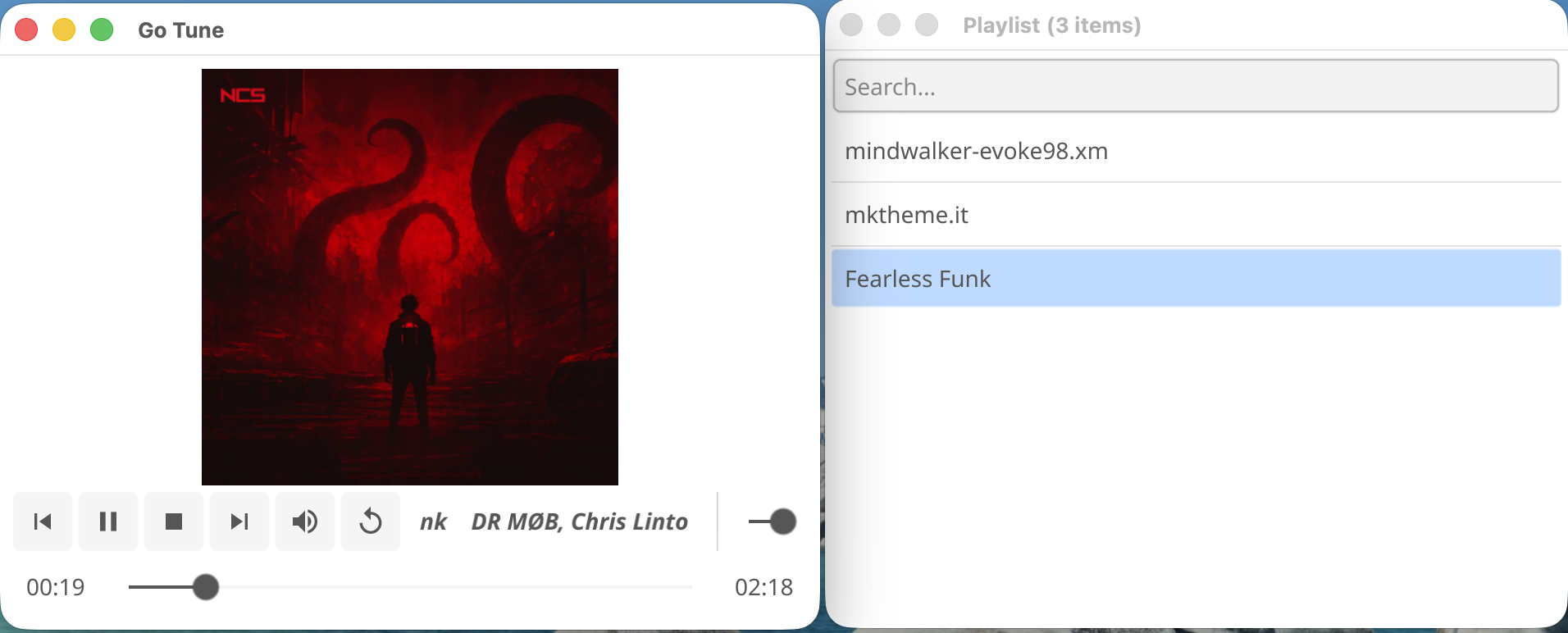

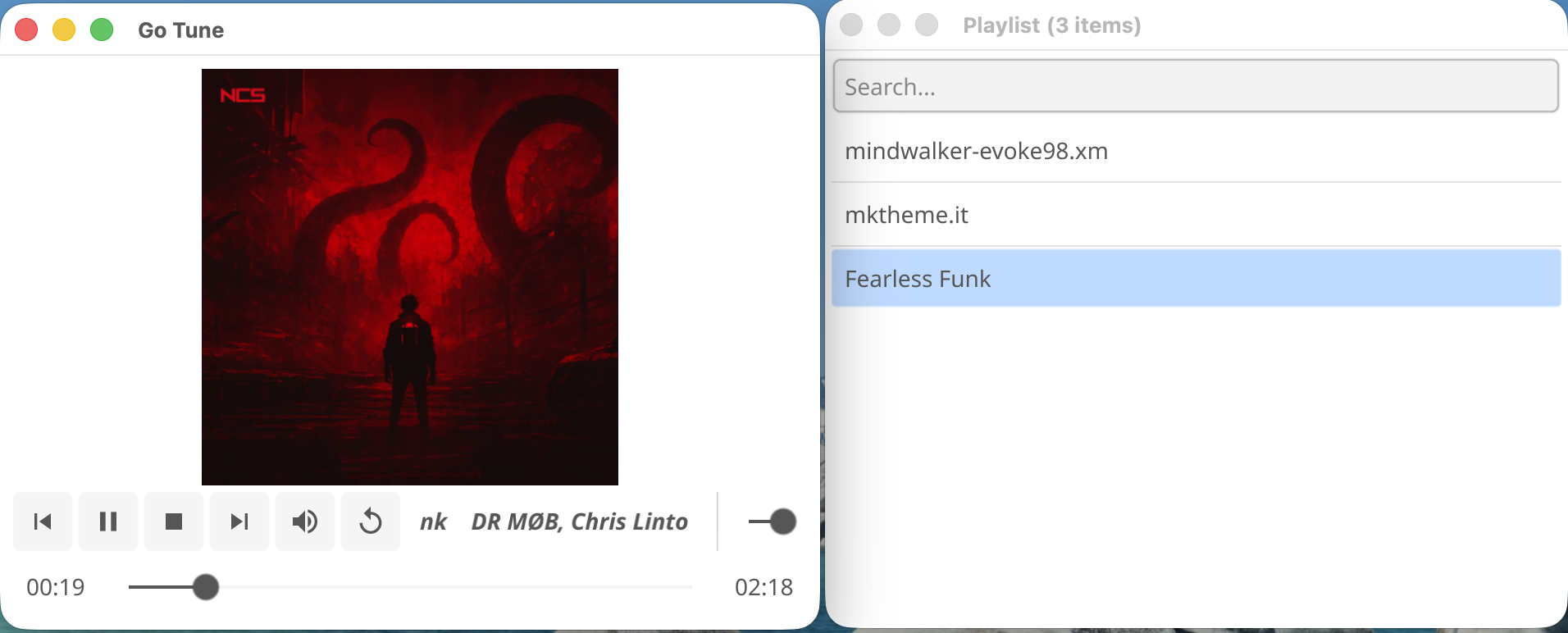

GoTune: Exploring Clean Architecture in Desktop Applications

Back in college, I built a Windows music player called Tejash Player using C and the Win32 API. It worked well enough to get published on Softpedia, but the code was a mess. UI tangled into business logic, no separation of concerns, impossible to test. But it played music, so I shipped it.

A decade later, I spend most of my time building backend systems with Clean Architecture and Domain-Driven Design. These patterns are second nature in server-side development. But I kept wondering: do they actually work for desktop applications? GUI frameworks manage state, event loops, and user interactions in ways that feel fundamentally different from handling HTTP requests. Would Clean Architecture help or just add ceremony?

When I found Fyne, a Go GUI framework, I decided to find out by rebuilding that old music player.

The First Attempt

My initial proof of concept came together over a few evenings. Basic playback worked. Playlists loaded. The UI was functional. But the code looked uncomfortably familiar: callbacks nested in callbacks, UI components directly manipulating audio state, testing impossible without running the full application. I had recreated the same architecture problems from college, just in Go instead of C.

Life got busy, and the project sat dormant for months. But in January 2026, I carved out time to actually explore how Clean Architecture adapts to desktop development.

What I Ended Up With

After a lot of iterative refactoring, I landed on this structure:

1

2

3

4

main.go -> app -> services -> ports <- adapters

| |

v v

domain (Fyne, BASS, SQLite)

The domain layer is pure Go: music tracks, playlists, and events as plain structs with no external dependencies. This code could run anywhere.

The ports layer defines contracts through interfaces. What does an audio engine need to do? What events can the system publish?

The service layer orchestrates business logic, depending only on domain models and port interfaces. No Fyne imports. No audio library imports.

The adapter layer is where Fyne, the BASS audio library, and SQLite live. These adapters implement port interfaces and translate between external dependencies and the domain.

How It Worked Out

Some patterns translated directly from backend work. Dependency injection works exactly as expected:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

type PlaybackService struct {

engine ports.AudioEngine

bus ports.EventBus

mu sync.RWMutex

}

func NewPlaybackService(engine ports.AudioEngine, bus ports.EventBus) *PlaybackService {

return &PlaybackService{

engine: engine,

bus: bus,

}

}

I can test PlaybackService by injecting mocks. No GUI required. No audio hardware required.

Domain events replaced the callback spaghetti:

1

2

3

4

5

type EventBus interface {

Publish(event domain.Event)

Subscribe(eventType domain.EventType, handler domain.EventHandler) domain.SubscriptionID

Unsubscribe(id domain.SubscriptionID)

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

const (

EventTrackLoaded EventType = "track.loaded"

EventTrackStarted EventType = "track.started"

EventTrackPaused EventType = "track.paused"

EventTrackStopped EventType = "track.stopped"

EventTrackCompleted EventType = "track.completed"

EventVolumeChanged EventType = "volume.changed"

// ... over 20 event types total

)

The playback service publishes TrackStartedEvent. The UI subscribes and updates the play button. The visualizer subscribes and starts animating. Neither knows the other exists. Same event-driven architecture I use for microservice communication, just within a single process.

Other patterns needed adjustment. State management is more complex than in stateless services. A music player has persistent state: current track, playback position, volume level, playlist order. This state lives in services but needs to reflect in the UI. Thread safety becomes a real concern since Fyne, like most GUI frameworks, requires UI updates from a specific thread.

The adapter layer ended up much thicker than in backend applications. GUI frameworks are opinionated about how you structure UI code. I used MVP (Model-View-Presenter) within the adapter layer to keep Fyne-specific code organized while ensuring presenters communicate through the event bus rather than directly manipulating services.

CGO also added complexity that pure Go services don’t have. The BASS audio library requires managing dynamic libraries across platforms: build tags, platform-specific initialization, careful resource cleanup. None of this exists when writing a REST API.

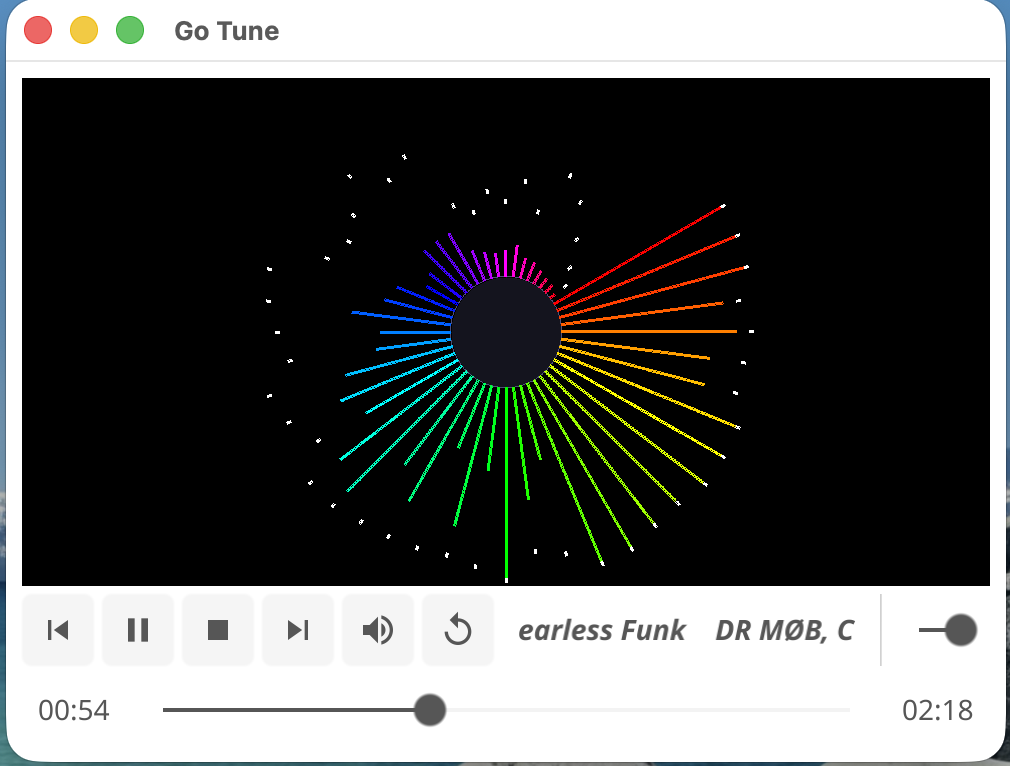

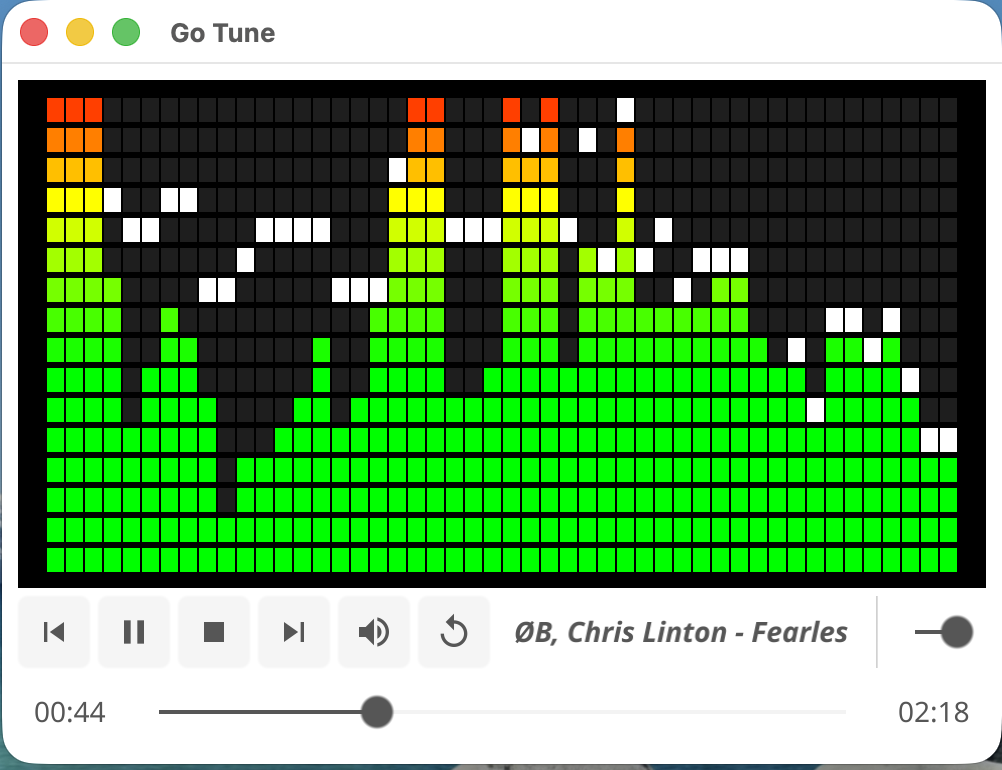

The Visualizer

One feature that proved the architecture was worth it: the audio visualizer. GoTune has eleven different visualizers that respond to music in real-time using FFT spectrum analysis.

Adding visualizers was straightforward because of the clean boundaries. The audio adapter exposes FFT data through a port interface. Visualizer adapters consume that data and render to Fyne canvases. The service layer doesn’t know visualizers exist. I could add more, remove them, or replace the entire visualization system without touching playback logic.

What I Learned

Clean Architecture does work for desktop applications, but with caveats.

Expect a larger adapter layer. GUI frameworks are substantial dependencies with strong opinions. Your adapters will do more heavy lifting than a typical HTTP handler.

Event-driven communication is necessary. Without events, you end up with circular dependencies between UI and services.

Thread safety matters more. Backend services often handle concurrency through request isolation. Desktop apps have background tasks, UI threads, and user events all interleaving.

Testing remains the biggest win. The ability to test business logic in isolation justifies the architectural investment.

From Tejash Player to GoTune, the core problem stayed the same: play music. But the tangled Win32 application is now a cleanly architected, cross-platform, testable codebase. The implementation details differ from backend services, the adapter layer is larger, and you need to think harder about state and threading. But the core benefits remain.

GoTune is open source: https://github.com/tejashwikalptaru/gotune