The journey of ssd1306xled: from debugging to open source maintenance

I had some ATtiny85 chips lying around my desk. These 8-pin microcontrollers are popular for small projects: 8KB of flash, 6 GPIO pins, and enough grunt to run simple games. I wanted to build something with them.

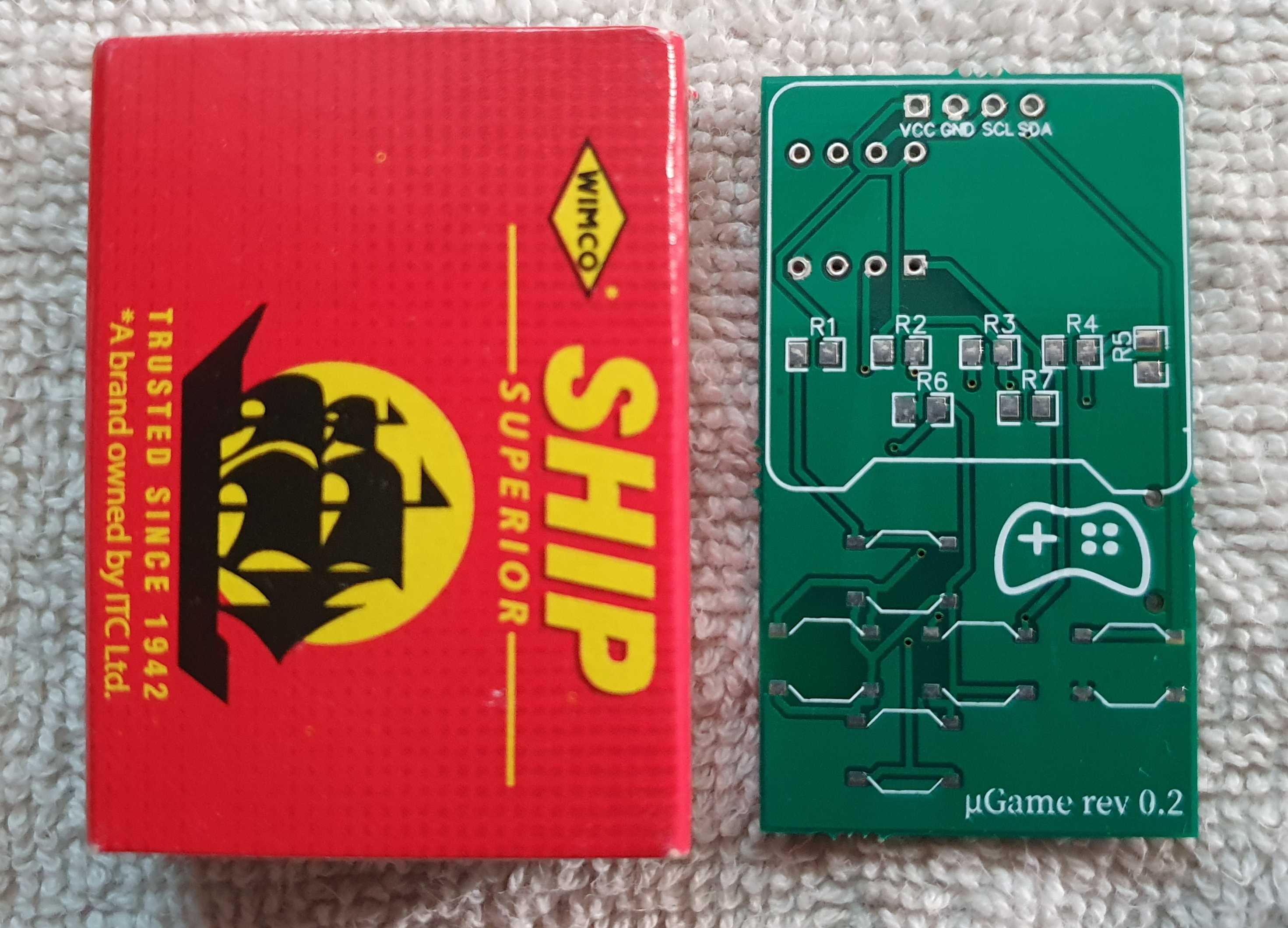

I found Daniel Champagne’s TinyJoypad project. Daniel had written several games for the ATtiny85’s constraints. Space shooters, platformers, puzzle games. All running on a chip smaller than a fingernail, displayed on a tiny OLED screen. I decided to build my own handheld console.

I wrote about the hardware build back in 2020. This post is about what happened after.

Nothing on screen

The project seemed straightforward. Wire up the ATtiny85, connect an SSD1306 OLED display, compile Daniel’s code, play some games. The code compiled without errors. I uploaded it to the chip.

The screen stayed black.

I tried different OLED modules. I had several from AliExpress and Banggood. All of them showed nothing. I connected the same screens to an Arduino Uno using Adafruit’s library. They all worked. The screens weren’t broken. The driver was.

Daniel’s code used ssd1306xled, a lightweight library designed for ATtiny chips. I pulled up the code and started reading.

Down the rabbit hole

The ssd1306xled library came from the TinuSaur project on BitBucket, written by Neven Boyanov. It’s a minimal OLED driver for resource-constrained microcontrollers, which made it a good fit for the ATtiny85’s 8KB flash limit.

My first suspicion was chip compatibility. Many OLED screens from Chinese suppliers claim to use the SSD1306 controller but actually use SSD1315 or SSH1106 variants. These chips are similar but have slightly different initialization sequences. The TinuSaur team had documented compatibility issues with mislabeled screens.

I cloned the original BitBucket repository and tried various initialization sequences. Nothing worked. I documented my findings in issue #5 on the TinuSaur project.

After more debugging, I realized the problem wasn’t the OLED chip variant at all. The I2C implementation was broken.

I2C is a communication protocol that lets microcontrollers talk to peripherals like OLED screens. The ATtiny85 doesn’t have dedicated I2C hardware. Instead, it has a Universal Serial Interface (USI) that can be configured to behave like I2C. Getting this configuration right is tricky. Timing matters. The sequence of start conditions, acknowledgments, and stop conditions has to be precise.

The ssd1306xled library’s USI configuration wasn’t generating proper I2C signals. The OLED controller never received valid commands because the protocol was malformed.

The fix

I couldn’t just switch to a different library. The ATtiny85 has 8KB of flash. Daniel’s games used about 6KB. That left roughly 2KB for everything else, including the OLED driver. Libraries like Adafruit’s SSD1306 or Tiny4kOled are well-tested, but they’re too large. They would push the compiled code over the 8KB limit.

I needed ssd1306xled to work. I needed its small footprint. I just needed the I2C implementation to function.

I found TinyI2C by David Johnson-Davies. Unlike the standard Arduino Wire library, TinyI2C was written for resource-constrained AVR chips. No buffers eating up RAM. No artificial limits on transfer sizes. Clean, minimal code that properly configured the USI for I2C communication.

The fix was surgical: replace ssd1306xled’s broken I2C functions with TinyI2C’s implementation.

The key functions:

I2CInit() configures the USI registers for two-wire mode. It sets up the data and clock pins with proper pull-ups and clears the status flags.

I2CStart() generates the I2C start condition by releasing SCL, pulling SDA low, then transmitting the slave address. It checks for acknowledgment from the OLED controller.

I2CTransfer() handles bit-by-bit clock generation. It toggles the clock via USICR, waits for SCL to stabilize, applies the timing delays defined by DELAY_T2TWI and DELAY_T4TWI, and continues until the transfer completes.

I2CStop() terminates communication with a proper stop condition: SDA low, release SCL, wait for stabilization, then release SDA.

The timing constants matter. The TWI_FAST_MODE flag controls whether the library uses standard (100kHz) or fast (400kHz) I2C timing. Getting these delays wrong means garbled communication or no communication at all.

I merged the working I2C code into ssd1306xled. Compiled. Uploaded.

The screen lit up. A space invader appeared. The game was running.

Sharing the fix

I created a fork on GitHub with attribution to Neven Boyanov for the original ssd1306xled driver and David Johnson-Davies for the I2C implementation.

I published the library to PlatformIO and the Arduino Library Manager. Added documentation with wiring diagrams, example code, and setup instructions. Wrote the blog post about the game console build.

Then I moved on to other projects.

Unexpected growth

I didn’t expect anyone else to use the library. I’d fixed my specific problem and shared the solution in case someone else hit the same wall. That seemed like enough.

Six years later, the repository has 81 stars and 8 forks. Developers email me with questions. Issues appear from people building projects I never imagined.

Why did it take off? The original library was broken for many users, not just me. Anyone trying to use ssd1306xled with cheap OLED screens would hit the same blank screen. My fork was the version that worked. The small size still mattered too. People building projects on the ATtiny85’s 8KB limit needed a small driver, and Adafruit’s library is too large for that. Clear documentation probably helped. Connection diagrams, example sketches, explanations of what the library does and how to use it.

The library fills a specific niche: minimal OLED driver for minimal microcontrollers. That niche is small but real.

Community contributions

The surprising part of maintaining this library has been watching other developers improve it in ways I never considered.

In July 2024, a developer named Lorandil submitted PR #7. They added ssd1306_tiny_init(), a new initialization function that saves 52 bytes of flash by skipping the initial screen fill. When you’re fighting for every byte on an ATtiny85, 52 bytes matters. Some projects were hitting the flash limit with the standard init function. Lorandil’s contribution let them fit.

In January 2026, Lorandil came back with PR #11: vertical addressing mode support. The SSD1306 can address pixels either horizontally (row by row) or vertically (column by column). The original library only supported horizontal mode. Vertical addressing lets you use different rendering approaches. The new ssd1306_tiny_init_vertical() function opened possibilities I hadn’t thought about when I first fixed the library.

There’s currently an open issue #17 from a user named Brian working on sprite animations. The library is being used for things beyond the simple static displays I originally built it for.

You solve your problem. You share your solution. Then people you’ve never met improve it for their problems. The result is better than what any one person would have built alone.

Professionalizing the project

For years, releasing new versions meant manually editing version numbers, creating GitHub releases, and hoping I didn’t forget something. As contributions increased, this became unsustainable. I needed automation.

I built three GitHub Actions workflows that handle the release process.

pr-checks.yml runs on every pull request. It validates library.json and library.properties to ensure they have required fields, checks that version numbers match between both files, compiles the library against the ATtiny85 target using PlatformIO, and builds all example sketches. If any check fails, the PR can’t be merged.

pr-changelog.yml uses Google’s Gemini API to generate changelogs. When a PR is opened or updated, the workflow extracts commit messages, changed files, and diffs. It sends this context to Gemini with instructions to summarize the changes. The generated changelog appears as a comment on the PR and gets saved as an artifact for release notes.

release.yml triggers when code merges to master. It identifies the merged PR, retrieves the AI-generated changelog, bumps the version number following semantic versioning, creates a git tag, generates a GitHub release, and publishes to the PlatformIO registry. A skip mechanism via PR labels prevents releases when merging non-code changes like documentation updates.

The CI/CD pipeline turned a hobby project into something that works like a professional library. Contributors can submit PRs knowing their code will be tested. Releases happen consistently without manual intervention.

What I learned

When code compiles but doesn’t work, the issue is often deeper than you expect. I spent time investigating chip compatibility when the real problem was the communication protocol. Trace problems to the lowest level.

The 8KB flash limit ruled out obvious solutions. I couldn’t use a larger, well-tested library. I had to fix the small library that fit. Constraints removed options and made the path forward clearer.

The fixed library credits Neven Boyanov’s original work and David Johnson-Davies’s I2C implementation. Being explicit about standing on others’ shoulders matters. People trust projects that credit their sources.

The README, example code, and wiring diagrams help users. They also help me when I return to the project after months away.

CI/CD reduces friction for contributions. When someone submits a PR, automated checks tell them if their code works. When I merge changes, automated releases handle versioning and publishing. Less manual work means more time for actual improvements.

The problem I solved wasn’t unique. Other developers had the same OLED screens, the same blank displays, the same frustration. Publishing my fix helped people I’ll never meet.

Six years later

What started as a weekend debugging session is now a maintained library with users around the world. The codebase is cleaner than what I originally wrote. The CI/CD pipeline is more sophisticated than some professional projects I’ve worked on. Contributors have added features I never imagined needing.

I still get notifications when someone opens an issue or submits a PR. Each one is a reminder that open source works through accumulation. Small fixes, modest improvements, better documentation. No single contribution is dramatic, but they compound over time.

If you’re building projects on ATtiny85 or similar constrained microcontrollers, the library is at github.com/tejashwikalptaru/ssd1306xled. If something doesn’t work, open an issue. If you have an improvement, submit a PR.

Thanks to Neven Boyanov for the original ssd1306xled, David Johnson-Davies for TinyI2C, Daniel Champagne for the TinyJoypad games that started this project, and everyone who has contributed code, reported issues, or just used the library to build something.